Pierre Poilievre and the Little Canadians

Examining a new Canadian political movement and where it will take the Conservative Party

Rishi Sunak, the U.K.’s prime minister, was supposed to be the normal one. He was the one who, after the bumbling Boris years and the terrible Truss episode, was going to be more like a Tory of old — a wealthy former banker who would get the economy back on track and, as he had for much of his political career, do his job quietly. For example, if you look into Sunak’s record before this October on LGBTQ issues, you’ll find very little beyond his abstention during two parliamentary votes on same-sex marriage. Otherwise, crickets.

But then.

“We shouldn’t get bullied into believing that people can be any sex they want to be. They can’t. A man is a man and a woman is a woman,” Sunak told his party during its annual conference in October. He then use a phrase now familiar to Canadians: “That’s just common sense.” Whose common sense? Not that of his party’s members, largely. One poll of 500 Tory members, obtained by a British journalist, revealed that respondents placed trans issues — that is, the rights rights of trans people, as well as their participation in sports — near the bottom of the list of their top priorities. Only three per cent cared about either topic. A spring YouGov poll similarly showed that only 25 per cent of those who voted Conservative in 2019 said they’re paying a lot or a fair amount of attention to trans issues coverage. As for Britons more generally, 64 per cent told a pollster this summer they think transgender people face at least a fair amount of discrimination. Nearly half agreed that things like passports should have options other than just “male” and “female”.

Those passports are blue now, by the way – no longer a deep European maroon. Not since Sunak’s party embraced the Little Englanders, the core ideological bloc that led the UK out of the EU.

Little Englanders were once a group in the 1800s that looked askance at Britain’s empire as costly and generally disadvantageous to the colonies. They also saw Canada specifically as a trade ally that took more than it gave. Back then, Little Englanders wanted more free trade, ostensibly, but specifically trade arrangements that would benefit England (less so Britain as a whole). More recently, the Little Englander has re-emerged in U.K. politics as something slightly different. The term now applies most obviously to the EU skeptics, but more broadly to a mentality that prefers to shut out the outside world. Little Englanders feel more English than British, are resentful of immigration, prone to racial prejudice, and unsure about equal opportunity. They are far from a real majority, but in recent years, they’ve been influential.

Take for example Nigel Farage, the British chauvinist – a modern-day Basil Fawlty who romanticizes the empire/Commonwealth, rails against so-called “woke” culture and gatekeepers, and whose (ultimately successful) campaign to have the U.K. exit the EU hinged, in part, on his pining for a blue passport. That Brexit campaign — brash, nationalist, and reactionary — tapped an anti-establishment perspective that cut a seam of support across party lines, creating a new identity amongst the electorate. For his work, Farage was kicked out of the Conservative Party, but Sunak now seems ready to let him back in. A formality, surely. Ever since the Tories realized, in the fallout of Brexit, that they could leverage the revived Little Englanders for enough support to win elections — tracking party policy further toward that mentality in successive years — it’s really been Farage’s party, and that of the Little Englanders.

Now it’s happening here.

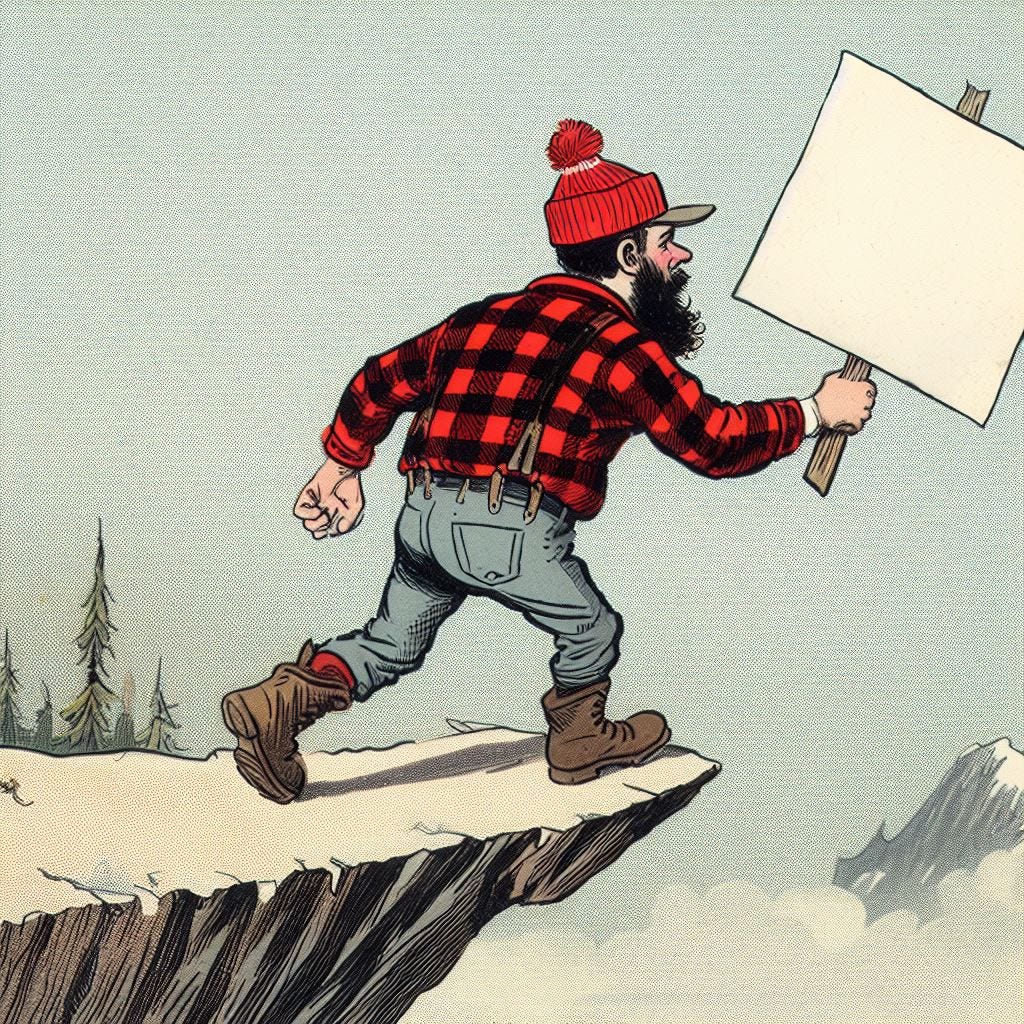

Canada’s Conservatives have been functionally Pierre Poilievre’s party for some time, even prior to his leadership. Under both Andrew Scheer and Erin O’Toole, Poilievre honed his act as a lib-trolling tweet-dunker, a role that won him accolades within his caucus and online, and pushed the party to the right. Scheer and O’Toole each tried, and failed, to follow him. Then came the pandemic. Where Farage used EU skepticism (or conspiracy) to link support across party lines in the U.K., Poilievre’s embrace of the anti-mask mandate movement, and his leveraging of its inherent anti-institutional sentiment – which similarly crosses the left-right spectrum – has allowed him to tap into broad resentment, build messaging that blames all ills on the government or its agencies, and foment a new kind of Canadian ideological and political actor: the Little Canadian.